HOW CAN WE HELP YOU? Call 1-800-TRY-CHOP

In This Section

Digging Deep Into Decisions to Treat Short Stature With Human Growth Hormone

By Nancy McCann

By Nancy McCann

Tall people are self-confident, successful, and have the world at their feet, according to our society’s biases and assumptions. This perception tends to elevate the pressure for parents, children, and clinicians to try human growth hormone (hGH) for treating idiopathic short stature (ISS) — children with severe short stature without an identifiable cause. But how short is severe enough to warrant hGH treatment, which can involve years of daily injections and exposure to potential side effects, at a cost of about $30,000 per patient per year?

And should choosing hGH treatment also be based on its potential to boost a child’s self-image and peer acceptance? Perhaps your middle-schooler is embarrassed that she’s always first in her size-ordered class photos, or your high school student is excluded from playing the sports he covets because his teammates tower over him.

These are some of the questions behind the research of Adda Grimberg, MD, pediatric endocrinologist and scientific director of the Diagnostic and Research Growth Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Grimberg is on a quest to improve the care of children with short stature by developing the evidence base, rather than relying on assumptions, about who seeks hGH treatment for short stature and why, and how much hGH treatment actually addresses their specific concerns.

With a recently funded National Institutes of Health grant, Dr. Grimberg and co-principal investigator, Victoria Miller, PhD, aim to drill down into what drives the decision-making involved in pursuing hGH treatment, by asking both parents and children their perceptions of short stature and their perceptions and expectations of treatment. The study further aims to discover factors that predict patient and parent satisfaction two years after their decision.

“It’s a shared decision-making process because short stature in and of itself is not a disease,” Dr. Grimberg said.

Determining Treatment

Physicians have prescribed hGH to treat children with growth hormone deficiency (GH) for the past 60 years, with both health benefits and significant increases in height. With the advent of recombinant (synthetic) hGH in 1985, supply became essentially unlimited, and a slippery slope ensued. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved hGH treatment for a growing list of medical conditions, and in 2003, the FDA approved it as a treatment for ISS, but not all children with ISS respond well to growth hormone treatment.

“The reason we as pediatricians are concerned about short stature or growth failure is that growth is a very sensitive sign of a child’s overall health,” Dr. Grimberg said. “There are many health conditions that can present with growth failure. It really is an excellent clinical clue that something could be going on.”

However, height itself is just one piece of the conundrum. Other factors include growth velocity, puberty status, overall health, and psychosocial stresses and burdens. When deciding if growth hormone treatment is warranted, physicians must first distinguish what’s healthy variance short stature versus an underlying problem. If an underlying problem does exist, it must be diagnosed and treated accordingly. Many of those conditions require treatments different from hGH.

For example, Dr. Grimberg spoke of a young female patient with florid growth failure whose pediatrician had dismissed her short stature as, “You’re short, you’re cute, you’re fine; don’t worry about it.” When in reality, the patient was suffering from untreated celiac disease for six years. Switching to a gluten-free diet helped her feel better, resume growing, and undergo puberty.

Once a clinician sorts out if the patient has short stature that’s not related to an identifiable problem, then they also must consider if the child is a late bloomer who is expected to reach a “normal” adult height on his/her own. But if the adult height prediction is on the short side, that’s when Dr. Grimberg has conversations with families and caregivers, keeping in mind social pressures for tallness typically weigh more heavily on boys.

“In society, there are some prejudices against shorter people — a phenomenon termed ‘heightism’ — so parents want to treat short stature to help their children avoid those stresses,” Dr. Grimberg said.

Despite the parents’ good intentions, she worries the children may be getting a different, and not so beneficial, message. They may internalize their parents’ pursuit of medical care and years of daily injections as a sign that they are “less than” or “abnormal” by virtue of their height.

“What if these boys and girls heard, ‘You are healthy, and height does not define who you are as a human being,’ instead of being made to feel something is wrong with them because they are shorter than what society dictates?” Dr. Grimberg said.

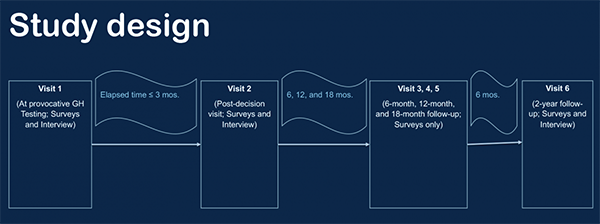

Helping her decode the psychology behind the decision-making process is Dr. Miller, a pediatric psychologist and director of Research of CHOP’s Craig-Dalsimer Division of Adolescent Medicine. As part of the NIH study, they plan to survey and interview parents and children independently every six months over a two-year span. The researchers are looking to discover the ways in which parent and child characteristics influence quality of life and self-esteem over time in youth with short stature who are either treated or untreated with growth hormone.

“The field knows very little, if anything, about how families approach the decision about growth hormone treatment, the factors they consider when making the decision, and whether and how children are involved,” Dr. Miller said. “Understanding children’s roles is critical because growth hormone treatment is considered elective in some cases and involves daily injections and potential side effects over the course of years — a burden that is borne by the child.”

Years of Research

Image credited by Adda Grimberg, MD and Victoria Miller, PhD.

This line of research has fascinated Dr. Grimberg for years. She started off by studying patterns in the referral and treatment of children with short stature, including disparities by gender, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomics. The findings, published in Scientific Reports in 2015 and other medical journals, also appeared in The New York Times. The new NIH grant is a next step that grew directly from her experience as the chair of the Pediatric Endocrine Society taskforce charged with writing the updated guidelines for pediatric hGH treatment.

Due to the rigorous evidence review of literature since recombinant hGH was introduced, the team discovered some “significant knowledge gaps,” Dr. Grimberg said. “We’ve been treating kids for over 30 years based on assumptions like increasing a child’s height with growth hormone will improve their quality of life or short stature really does serve as a detriment to quality of life. These are more assumptions rather than actually proven facts — and that lies at the crux of the long-standing debate about hGH treatment for idiopathic short stature.”