HOW CAN WE HELP YOU? Call 1-800-TRY-CHOP

In This Section

A Giant in the Field of Growth: Q&A With Michael Levine, MD

Michael Levine, MD, medical director of the Center for Bone Health, was recognized with lifetime achievement awards from both the Pediatric Endocrine Society and the Human Growth Foundation.

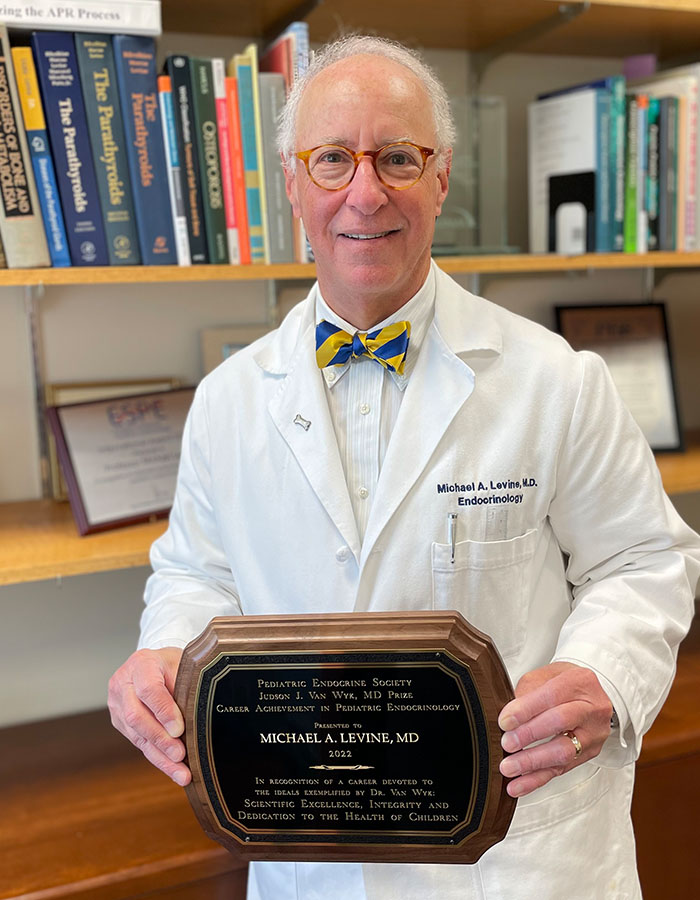

Editor’s Note: Michael Levine, MD, FAAP, FACP, FACE, medical director of the Center for Bone Health at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, has been recognized with — not one, but two — lifetime achievement awards for his outstanding work in the field of pediatric endocrinology. The Pediatric Endocrine Society (PES) presented Dr. Levine with their most prestigious award, the Judson J. Van Wyk Prize, which stands in tribute to an outstanding leader whose career is marked by scientific excellence, leadership, and dedication to the health of children. Also honoring Dr. Levine is the Human Growth Foundation, which named him the 2021 Lifetime Achievement Honoree. See this HGF tribute video that captures Dr. Levine’s notable career, and read on to learn what these honors mean to him.

What do these lifetime achievement awards represent to you?

There can be no greater distinction for me than to be recognized by my peers for advancing the care of children with endocrine disorders. My life’s work has been focused on improving the way we diagnose disorders of the endocrine system in children, advancing our understanding of the pathophysiology of these disorders, and to use this information to develop and use therapeutics to optimize the clinical outcome for each patient. The goal is to personalize care so every child can reach their full potential.

In my own area, the genetics of endocrine disorders and with particular emphasis on disorders of bone and mineral metabolism, people often ask me, “What does it matter if a child has a problem related to their bones?” I always point out that “bones” represent the skeleton, the framework of the body. A normal skeleton is needed for proper growth, and when you think about it, growth is what childhood is all about. Everything we do in pediatric endocrinology is focused on optimizing growth of the child. Every one of the conditions that affect children as a manifestation of an endocrine disorder impairs growth potential. And so everything we do is about growth. And that’s the definition of childhood: growth and development.

Dr. Michael Levine shown here with the 2022 Pediatric Endocrine Society’s Career Achievement award.

What led you to choose a focus in pediatric endocrinology?

I started out training in internal medicine at Johns Hopkins, but when I went to the National Institutes of Health for my fellowship training, I was part of a program in adult and pediatric endocrinology. I subsequently extended my training to take a fellowship at NIH in genetics, which further expanded my interest in pediatric disorders. Nevertheless, when I returned to Johns Hopkins to join the faculty, my primary appointment was in the Department of Medicine, which was led at that time by Dr. Victor McKusick, a geneticist. My faculty position at Johns Hopkins was in the Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, so I focused on disorders of bone and mineral metabolism in adults.

But my research interests were really focused on growth and development of the skeleton and disorders of mineralization. My research interests led me to spend time with endocrinologists and geneticists in the Department of Pediatrics, and over time I realized that Pediatrics was really where I needed to be in order to understand the basis for the endocrine diseases I was interested in. This eureka moment led me to the decision to start working in the Pediatric Endocrine clinic at Hopkins.

At that time, the late Dr. Harold Harrison was running a spectacular bone and mineral clinic for kids with rickets, skeletal dysplasias, and disorders of mineral metabolism. I was amazed by his knowledge, the way he interacted with his young patients, his care and commitment — and doing all of this in the context of a research career. I realized this is what I wanted to do. Over a period of time, I transitioned from adult endocrinology into pediatric endocrinology. And that transition really occurred in 1998, when I became director of the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at Johns Hopkins, and I’ve been a card-carrying pediatric endocrinologist ever since.

What have you found most interesting about how science has evolved since you began your career?

When I was a fellow at the NIH, bone and mineral metabolism was just beginning to move into the molecular age. Assays that allowed us to measure serum levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH) were just being developed. I joined the laboratory of Dr. Gerry Aurbach, who had recently characterized the amino acid sequence of PTH, at the dawn of immunoassays. We were just beginning to understand the protein machinery that PTH used to transmit signals across the plasma membranes of its target cells, and learning about the second messenger, cyclic AMP.

Flash forward 40 years, and I now run a laboratory that uses the tools of next generation sequencing to understand how these proteins operate! Our ability to measure things and to identify abnormal molecules has increased multifold. And with each advance in technology, comes the ability to ask more granular questions. You can get closer to actual molecular defect. Knowing molecular defects enables you to understand critical pathways and to open new doors to therapeutic intervention. Having the ability to use contemporary tools of molecular biology in order to understand clinical problems, makes the process of therapeutic discovery far more rapid and direct. That’s what’s been exciting over the past 40 years — moving from the ability to just measure whether a serum level of PTH is elevated or not to now being able to understand why on a genetic basis, the level of PTH is high or low.

I’ve been fortunate to be able to recruit many patients with parathyroid problems into my research protocols, and through sequencing, we’ve been able to determine the precise genetic mutation and identify novel genes that cause these phenotypes — things that I would never have been able to imagine when I first began my career.

Is there a particular aspect of your work or a specific project you are most proud of?

The longest project I’ve worked on has been pseudohypoparathyroidism, a genetic disorder in which the body fails to respond to parathyroid hormone. I made the original discovery that affected patients have a defect in an important G protein and later identified the first mutations in the abnormal gene. We defined the clinical spectrum of the disorder and categorized it into several different forms of pseudohypoparathyroidism and created mouse models that allowed us and others to explore the role of G protein signaling.

Our work stimulated others to enter the field, and I’m very proud of that as well, because others working in this field have been able to complement my work and advance our understanding of hormone resistance in patients of pseudohypoparathyroidism. What we know today is not the result of my work alone, it’s my work and the work, I believe, I stimulated others to pursue.

Any additional thoughts?

Since coming to CHOP, I’ve been able to realize my dream of working in the field of rickets and vitamin D, which has been enormously rewarding. Children with rickets don’t grow well because of a disturbance in the growth plates of their long bones. Their bones also lack sufficient calcium and phosphorus to become properly mineralized. The bones are weak and become deformed, and it’s very painful. In most cases it’s because of simple nutritional deficiency of vitamin D, which surprisingly continues to be a problem in the United States and throughout the world.

We’ve been able to identify new genes that cause specific forms of rickets that are amenable to precision treatment. We’ve been trying to develop the notion that every patient is unique and there may be genetic basis for variation in vitamin D requirements from one person to another. We’ve been working to better understand the genetics of vitamin D requirements and activation so that we can help develop vitamin D intakes that can be applied more broadly and be more effective at optimizing mineral metabolism and preventing rickets.

It’s been an honor for me to be able to take care of children, and it’s been enormously gratifying. If you do something to help an adult — you get a thank you. But if you do something to help a child, it’s a legacy — the investment continues for decades. The impact is so much greater. How much more gratifying can it be than to do something that improves 50 or 60 years of someone’s life?